Who Will Own the Future of Regenerative Coffee (pt. II)

In Part 1, we surveyed new research into coffee varietals, the story of the international coffee trade in the 20th century, and the consolidation of major firms toward the end of the century. In this second part, we trace the fallout from those develops and ask how they will impact the future of coffee production.

Genetic Diversity, Corporate Consolidation

All of this brings us back to World Coffee Research. Their membership page boasts dozens of well-known coffee brands that have come together to fund the “future of coffee.” Of the top twelve donors, only one American company is listed that wasn’t named in the above list— Allegro Coffee, which is owned by Amazon by way of Whole Foods (to be fair, there are several independent European and Japanese companies).

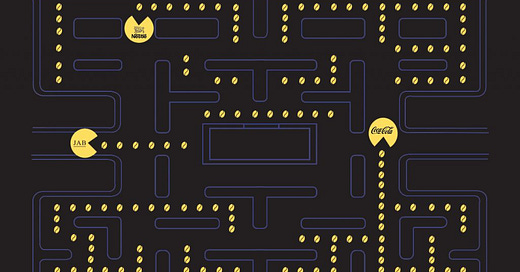

Scanning down the list, we see many names that are subsidiaries of larger corporate portfolios, essentially double-counting the actual diversity of corporate support for WCR from a capital perspective.

For example, Keurig Dr. Pepper and JDE Peet’s are each listed as donors, as well as Intelligentsia, which is a member of the JDE Peet’s portfolio. Similarly, green coffee importers InterAmerican, Atlas, and Rothfos Corp. have each contributed to the WCR fund. All three are owned by Hans Neumann Kaffee Groupe. There are likely other such instances in the list.

There are no simple interpretations of this industry-wide consolidation trend, or what it means for the future of coffee. It’s tempting to take a cynical view of what could well amount to a sophisticated greenwashing of the climate crisis in coffee.

It would be easy to point out, for example, the hypocrisy of a Keurig- Dr. Pepper making environmental claims while pushing sales of their single-use plastics-based coffee pods.

It would be understandable to doubt the sustainability claims of a company like Nestle, who touts its work to provide access to clean water while it stands accused of draining public aquifers to then sell as bottled water.

And, you couldn’t fault one for being skeptical of Starbucks’ sustainability claims when they have had repeated issues self-enforcing their own ethical sourcing criteria.

Yet, I don’t think that point of view gives credit to the genuine good will that exists at all levels of these corporations to do the right thing, both for the environment and for the coffee farmers who work the land. Just go on the websites of any of these businesses and you’ll inevitably find some page dedicated to the company’s specific program or overall ethos for working to improve the lives of coffee farmers. These programs are designed and championed by really existing passionate people within these organizations. They aren’t just corporate fronts.

But if this good will really does exist, then an interesting question arises: If these multinational corporations care so much about the lives and futures of smallholder coffee farmers, then why, in the era of trade liberalization, when these firms came to dominate more of the supply chain than ever before, and the firms profited more than ever before, did coffee farmers suffer more than ever?

With the end of the International Coffee Agreement and the resulting “liberalization” of the international coffee market, firms based in consuming countries (i.e., the U.S. and Europe) came to exercise more control over the market; they retained a higher percentage of the profits from the movement of coffee through the market, and prices were lower overall.

This situation created multiple “price crises” which coffee farmers and their children experienced as times of hunger and poverty. Where was the good will for farmer livelihoods then?

The above chart shows the C-Market, or average market price, for green coffee from the ICA period (1965-1989) through the new, liberalized era of coffee trading (1990-today). We can see clearly here that prices paid to farmers have been lower in real terms to farmers in the post- ICA era.

With the end of the ICA quota-system, Brazil, and later Vietnam, flooded the world market with cheap Arabica and Robusta coffee. The international firms were happy to substitute these beans into their blends to serve up lower-quality but more profitable coffee to consumers. All this considered, we need to be realistic about how far the good will of the large coffee firms extends and remember that with them, profits always come first.

Who Will Develop Climate Solutions for Coffee, and for Whose Benefit?

Despite my reservations, I’m optimistic about the future of regenerative agriculture and the positive effects of these megafirms investing into climate solutions for coffee. Undoubtedly, the amount of capital and brainpower flowing into the sector will move the needle toward a more sustainable industry in some form or fashion.

However, I’m still concerned about the top-heavy consolidation in the industry. The supply chain is more and more dominated by firms whose decision-making power is in the hands of corporate boards in Europe and the United States, far removed from the daily lives of the farmers who steward the coffee lands.

The climate solutions that these firms develop will have to adhere to a corporate logic bound by quarterly reports and shareholder profits, and it’s not clear if this framework can produce the best results for the environment or for farmers.

Although the global coffee trade has evolved considerably in the past several hundred years, the balance of power between the old colonizing countries and the former colonies is not so dramatically different in one key point: the relationship between these large companies and the coffee producing countries is based on resource extraction for profit.

With this in mind, it’s easy to see their investment in World Coffee Research’s work as simply investing in their own supply chains, especially considering the control that these firms exercise at the farm level. When the new, climate-adapted varietals are available, will anyone be surprised when the top donors to the WCR are first in line to receive them?

Our environmental issues are not fully separable from issues of economics or political power. That’s why we founded Biota as an exploration of what it means to move away from an economics of extraction to an economics of regeneration. Furthermore, we knew from the start that these solutions must be developed hand-in-hand with the farmers who grow the coffee and work the land.

In the end, we do need new varietals in coffee, but we also need a new paradigm for growing coffee. Otherwise, the same problems of today— disease outbreaks, climate disruption, low farmer profitability— will inevitably resurge.

We start from the permaculture principal that values diversity inherently—diversity of soil life, biodiversity aboveground, as well as diversity of ideas and approaches to solving our urgent problems.